Chopin’s Pedagogy: A Practical Approach 蕭邦(Chopin)的教學法:在 MTNA 全國大會上發表的實用方法

作者: David Korevaar,科羅拉多大學

Presentation delivered at the MTNA National Convention, Pedagogy Saturday, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 2010

Resources

I see this paper as essentially practical: Chopin’s pedagogical ideas are ideas that I and many other teachers use regularly. Rereading Jean-Jacques Eigeldinger’s important book Chopin as Pianist and Teacher reminds me of how much Chopin’s ideas resonate with the way I teach, the way I was taught, and the way that I try to play. This important source collects most of the information that we have on Chopin’s teaching in a convenient and user-friendly format. The book draws from Chopin’s memoranda books, correspondence, and his fragmentary “Projet de méthode” as well as the annotated scores and statements of his students and associates.

我認為這篇論文本質上是實用的:蕭邦(Chopin)的教學理念是我和許多其他教師經常使用的理念。重讀讓-雅克·艾格爾丁格(Jean-Jacques Eigeldinger) 的 重要著作《作為鋼琴家和教師的蕭邦(Chopin)》讓我想起了蕭邦的思想與我的教學方式、我被教導的方式以及我嘗試演奏的方式有多少共鳴。這個重要的資源以方便和用戶友好的格式收集了我們掌握的關於蕭邦(Chopin)教學的大部分信息。這本書取自肖邦的備忘錄、信件和他的零碎的“方法計劃”,以及他的學生和同事的註釋樂譜和陳述。

Chopin’s approach to teaching was original and individual: as he had been himself largely self-taught, and thus not part of any “school” of learning or teaching, he was to some extent free of the technical dogmas of his contemporaries. He saw technique in an essentially musical way, and his teaching emphasized sound production first, technique second. In his sketch for a method, he writes, “One needs only to study a certain positioning of the hand in relation to the keys to obtain with ease the most beautiful quality of sound, to know how to play long notes and short notes and [to attain] unlimited dexterity.” “A well-formed technique, it seems to me, [is one] that can control and vary a beautiful sound quality.” (Quoted in Eigeldinger, 16-17).

蕭邦(Chopin)的教學方法是獨創的和個人的:由於他基本上是自學成才,因此不屬於任何“學派”的學習或教學,他在某種程度上擺脫了同時代人的技術教條。他從本質上以音樂的方式看待技術,他的教學首先強調聲音的產生,其次是技術。在他的方法概述中,他寫道,“一個人只需要研究手相對於琴鍵的特定位置,就可以輕鬆獲得最優美的音質,知道如何演奏長音符和短音符以及 [獲得]無限的靈活性。” “在我看來,一種結構良好的技術 [is one] 可以控制和改變優美的音質。” (引自Eigeldinger,16-17)。

Chopin spent a great deal of his time on teaching, unlike Liszt who, at least in the 1830s, had no desire to be known as a teacher. Chopin’s teaching was his primary means of support once he settled in Paris (1832-1849). In fact, he seldom performed after 1835, and was not particularly interested in teaching his students to perform. (Eigeldinger, 5). He told one pupil, “Concerts are never real music; you have to give up the idea of hearing in them the most beautiful things of art.” Contemporaries (students and associates) mentioned that Chopin himself was at his best as a performer in private because of his nervousness.

蕭邦(Chopin)將大量時間花在教學上,不像李斯特,至少在 1830 年代,李斯特不想被稱為教師。肖邦定居巴黎後(1832-1849 年),他的主要生活來源是肖邦的教學。事實上,他在 1835 年以後就很少表演了,而且對教學生表演也不是特別感興趣。(Eigeldinger,5)。他對一名學生說:“音樂會從來都不是真正的音樂;你必須放棄從中聽到最美麗的藝術東西的想法。” 同時代的人(學生和同事)提到,由於緊張,蕭邦(Chopin)本人在私人表演中處於最佳狀態。

Students were given one to three lessons a week, officially of 45 minutes each, but not always so short if the pupils were talented. He taught 5 pupils per day. He was much in demand as a teacher of wealthy women, who paid 20 gold francs per lesson (this was a lot of money) or 30 if he came to them (Eigeldinger, 6-7). The more talented pupils seem to have paid less; sometimes nothing at all.

每週給學生上一到三節課,官方規定每節課 45 分鐘,但如果學生有才華,時間並不總是那麼短。他每天教5個學生。作為富有女性的老師,他很受歡迎,她們每節課支付 20 金法郎(這是一大筆錢),如果他來找她們,則支付 30 金法郎(Eigeldinger,6-7)。越有才華的學生似乎付出的越少; 有時什麼都沒有。

Of Chopin’s roughly 150 pupils, only a few are of great interest to us, both because of their later success as performers and teachers and because of their recollections. Clara Wieck’s description of George Mathias, one of Chopin’s most important disciples because of his later career as a professor at the Paris Conservatoire, illustrates Chopin’s teaching well. In an 1839 letter to her father, Clara writes of the twelve-year-old Mathias: “[he] has received an excellent education, has wonderfully flexible fingers, plays all of Chopin, and there is nothing he cannot do. In fact he outshines all the keyboard strummers around here. Remarkably, he has never worked more than one hour per day. His father, an extremely reasonable man, does not make him play in public and is not one of those fathers who deify their children.” (Quoted in Eigeldinger, 170). Understanding that Clara’s father was something of a slave-driver and insisted on her practicing a lot and performing all the time, these words are quite interesting! We have this description of the adult Mathias’ playing by his contemporary Marmontel: “Under his agile and firm fingers, the most arduous passages retain their transparent clarity; one never senses fatigue, or is aware of the difficulties overcome. The expression, controlled by the principles of style and good taste, is never exaggerated.” (Ibid.) Of Chopin’s teaching of rubato, Mathias himself said, “you can be early, you can be late, the hands are not in phase; then you make a compensation which re-establishes the ensemble. In Weber’s music, for example, Chopin recommended this way of playing.” (49-50). Mathias went on to teach at the Conservatoire (for over 30 years, beginning 1862) (Ibid.) His two most important pupils were Isidore Philipp and Raoul Pugno. (Interesting examples of Pugno’s playing are available on YouTube, including the A-flat Impromptu, the F-sharp Nocturne, and the Berceuse; see Resources page.)

在蕭邦(Chopin)的大約 150 名學生中,只有少數人引起了我們的極大興趣,這既是因為他們後來作為表演者和教師的成功,也因為他們的回憶。 克拉拉維克的 喬治·馬蒂亞斯是肖邦最重要的弟子之一,後來在巴黎音樂學院擔任教授,對他的描述很好地說明了肖邦的教學。在 1839 年寫給父親的一封信中,克拉拉這樣描述 12 歲的馬蒂亞斯:“[他] 受過良好的教育,手指非常靈活,彈奏所有的蕭邦(Chopin)作品,沒有什麼是他做不到的。事實上,他勝過這裡所有的鍵盤手。值得注意的是,他每天的工作時間從未超過一個小時。他的父親是一個非常通情達理的人,不會讓他在公共場合玩耍,也不是那些神化孩子的父親之一。” (引自Eigeldinger,170)。了解克拉拉的父親是個奴隸販子還堅持要她一直多練多演,這話還蠻有意思的!與他同時代的馬爾蒙泰爾對成年馬蒂亞斯的演奏有這樣的描述:“在他靈活而堅定的手指下,最艱鉅的段落保持透明清晰;一個人永遠不會感到疲勞,也不會意識到克服的困難。表達,由風格和品位的原則,絕不誇張。” (同上)關於肖邦的rubato教學,Mathias 自己說:“你可以早,也可以晚,雙手不同步;然後你做出補償,重新建立合奏。例如,在韋伯的音樂中,蕭邦(Chopin)推薦了這種演奏方式。” (49-50)。 Mathias 繼續在音樂學院任教(30 多年,從 1862 年開始)(同上。)他的兩個最重要的學生是Isidore Philipp 和Raoul Pugno。 (有關Pugno 演奏的有趣示例可在 YouTube 上找到,包括降 A 的即興曲、升 F 的夜曲和 Berceuse;請參閱參考資料頁面。)

Carl Mikuli was another important pupil. In his preface to his edition of Chopin’s works, he writes,

A true pianist’s hand, not so much large as extremely supple, enabled [Chopin] to arpeggiate the most widely disposed harmonies and to perform sweeping passagework, which he introduced into the idiom of the piano as something never before dared, and all without the slightest exertion being evident, just as overall an agreeable freedom and ease particularly characterized his playing. At the same time, the tone that he could draw from the instrument was always huge, especially in the cantabiles; only Field could compare with him in this respect. A virile, noble energy – energy without rawness – lent an overwhelming effect to the appropriate passages, just as elsewhere he could enrapture the listener through the tenderness – tenderness without affectation of his soulful renditions. With all his intense personal warmth, his playing was nevertheless always moderate, chaste, refined, and occasionally even austerely reserved. Unfortunately, in the trend of modern pianism, these fine distinctions, like so many others belonging to an ideal art movement, are thrown into the attic of “superseded ideas” that hinder progress, and a naked display of strength, not considering the capacity of the instrument, not even striving for the beauty of the sound to be shaped, today passes for large tone and energetic expression.

Mikuli’s pupils included Moriz Rosenthal and Raoul Koczalski.

(See Resources page for examples of their playing on YouTube)

卡爾米庫利是 另一個重要的學生。在他為蕭邦(Chopin)作品編撰的序言中,他寫道:

一個真正的鋼琴家的手,與其說是大,不如說是極其柔軟,使蕭邦(Chopin)能夠彈奏琶音 最廣泛的和聲,並進行全面的段落工作,他以前所未有的方式將其引入鋼琴的習語中,並且毫不費力地表現出來,正如總體上令人愉快的自由和輕鬆是他演奏的特點一樣。同時,他能從樂器中調出的音色總是很大,尤其是在如歌中;在這方面,只有菲爾德能與他相提並論。一種陽剛、高貴的能量——不生硬的能量——給適當的段落帶來了壓倒性的效果,就像在其他地方一樣,他可以通過溫柔來吸引聽眾——溫柔而不影響他深情的演繹。儘管他有著強烈的個人熱情,但他的演奏總是溫和、純潔、精緻,有時甚至是樸素的內斂。很遺憾,

Mikuli 的 學生包括Moriz Rosenthal 和Raoul Koczalski。

( 有關他們在 YouTube 上播放的示例,請參閱資源頁面)

Chopin’s philosophy of teaching springs from the idea of music as a language, which had become standard by Chopin’s time. Chopin was said to have frequently incorporated language as a metaphor in his teaching. In the sketch for a method, Chopin made a list of attempts at defining music: (Eigeldinger, 195)

The art that manifests itself through sounds is called music.

The art of expressing one’s thoughts through sounds.

The art of handling sounds.

Thought expressed through sounds.

The expression of our perceptions through sounds.

The expression of thought through sounds.

The manifestation of our feelings through sounds.

The indefinite (indeterminate) language of men is sound.

The indefinite language music.

Word is born of sound—sound before word.

Word: a certain modification of sound.

We use sounds to make music just as we use words to make a language.

The idea of “musical declamation” also relates to Chopin’s interest in bel canto. Chopin is known to have frequently advised his pupils to listen to great singers of the time (Eigeldinger 14).

肖邦的教學理念源於音樂作為一種語言的理念,這在肖邦時代已經成為標準。據說肖邦在他的教學中經常將語言作為隱喻。在方法草圖中,肖邦列出了定義音樂的嘗試:(Eigeldinger, 195)

通過聲音表現出來的藝術叫做音樂。

通過聲音表達思想的藝術。

處理聲音的藝術。

通過聲音表達思想。

通過聲音表達我們的感知。

通過聲音表達思想。

通過聲音表達我們的感受。

人的不定(不確定)語言是健全的。

不確定的語言音樂。

詞生於音——音先於詞。

詞:音的一定修飾。

我們用聲音來創作音樂,就像我們用文字來創作語言一樣。

“音樂朗誦”的理念也與肖邦對美聲唱法 的興趣有關 。 眾所周知,肖邦經常建議他的學生聽當時偉大歌手的演奏 ( Eigeldinger 14)。

Chopin placed great emphasis on musical practice. In contrast to Liszt, Thalberg, and other virtuosi known for having their students focus on finger exercises, or pianistic “acrobatics,” as Chopin said, Chopin taught mostly from the music itself. That said, assigned repertoire did include Clementi’s Preludes and Exercises, as well as Gradus ad Parnasssum, evidently in order to develop even scales in particular. He also liked to teach some of Moscheles’ etudes – the most “musical” etudes before Chopin’s own. A-flat major seemed a particular favorite—the Clementi Exercise in that key and also the Moscheles Etude in A-flat (op. 70, no. 15) are both mentioned by pupils. Marie Roubaud, who had 18 lessons with him in 1847-48, studied the A-flat major sonatas of Beethoven (op. 26) and Weber (no. 2) with Chopin. (Eigeldinger, 61, 178). Chopin was also said to have played FieldÕs A-flat major Concerto particularly beautifully. (Examples: Clementi Exercise in A-flat major; Moscheles Etude in A-flat major, op. 70, no. 9.)

肖邦非常重視音樂 實踐。與李斯特、塔爾伯格和其他以讓學生專注於手指練習或如肖邦所說的鋼琴“雜技”而聞名的演奏家不同,肖邦主要從音樂本身進行教學。也就是說,分配的曲目確實包括金文泰的 前奏曲和練習曲,以及Gradus ad Parnasssum,顯然是為了特別發展均勻的音階。他還喜歡教授一些莫謝萊斯的練習曲——比肖邦的練習曲更“有音樂性”。降 A 大調似乎特別受歡迎——該調中的Clementi Exercise 以及Moscheles 降A練習曲(op. 70, no. 15)都被學生提到。 瑪麗· 魯博 ( Marie Roubaud) 在 1847-48 年間與他一起上了 18 堂課,她與肖邦一起學習了貝多芬 (op. 26) 和韋伯 (no. 2) 的降 A 大調奏鳴曲。(Eigeldinger,61、178)。據說肖邦還演奏了菲爾德的降 A 大調協奏曲,特別優美。(示例:Clementi Exercise in A-flat major;Moscheles Etude in A-flat major,作品 70,第 9 首。)

Mikuli mentions Cramer studies as part of the curriculum as well, but it seems these were only for the less advanced pupils and were seldom assigned in actuality. Chopin was known to reserve his own works (and especially the Etudes and the larger scale works) for the most advanced pupils. His own practicing and teaching of Bach is well documented, with special emphasis on the Well-Tempered Clavier – apparently the only music that he brought along to practice himself on the trip to Majorca with George Sand. (That trip resulted in the composition of the Preludes, op. 28.) According to his student Camille O’Meara (Dubois), he said at their last meeting in 1848 “always practice Bach—this will be your best means of progress” (Eigeldinger 61). George Mathias reported that Clementi, Bach and Field were the composers given to new students.

Mikuli 也提到 Cramer 研究作為課程的一部分,但這些似乎只針對後進生,實際上很少分配。眾所周知,肖邦會為最高級的學生保留他自己的作品(尤其是練習曲和大型作品)。他自己的巴赫練習和教學有據可查,其中特別強調平均律鍵盤——顯然是他在與喬治·桑去馬略卡島旅行時隨身攜帶的唯一用來練習的音樂。(那次旅行促成了前奏曲 op. 28 的創作。)根據他的學生 Camille O’Meara (Dubois) 的說法,他在 1848 年的最後一次會議上說:“永遠練習巴赫——這將是你進步的最佳方式” (Eigeldinger 61)。 George Mathias 報導說克萊門蒂、巴赫和菲爾德是給新生的作曲家。

Chopin encouraged short practice sessions. Madame Dubois (Camille O’Meara) reported: “One day he heard me say that I practiced six hours a day. He became quite angry, and forbade me to practice more than three hours.” (Eigeldinger 27). Another student wrote: “He always advised the pupil not to work for too long at a stretch and to intermit between hours of work by reading a good book, by looking at masterpieces of art, or by taking an invigorating walk.”

肖邦鼓勵短期練習。杜波依斯夫人(卡米爾奧米拉 Camille O’Meara)報導說:“有一天他聽到我說我每天練習六個小時。他非常生氣,並禁止我練習超過三個小時。” (Eigeldinger 27)。 另一名學生寫道:“他總是建議學生不要一口氣工作太久,在工作之間通過閱讀一本好書、欣賞藝術傑作或散散步來提神。”

Chopin, beyond the basic level, was not very interested in purely “technical” exercises. In general, he advocated an approach that avoided brute force solutions to technical problems. Mikuli offers the following example, writing that, “In complete opposition to Chopin, Liszt maintains that the fingers should be strengthened by working on an instrument with a heavy, resistant touch, continually repeating the required exercises until one is completely exhausted and incapable of going on. Chopin wanted absolutely nothing to do with such a gymnastic treatment of the piano.” And: “Chopin invented a completely new method of piano playing that permitted him to reduce technical exercises to a minimum.” (Eigeldinger 27). In light of these remarks, it is hardly surprising that Chopin preferred the Pleyel pianos, which had a lighter and more responsive touch than the Erards that Liszt preferred.

超出基礎水平的肖邦對純粹的“技術”練習不太感興趣。總的來說,他提倡一種避免使用蠻力解決技術問題的方法。Mikuli 提供了以下示例,寫道:“與肖邦完全相反,李斯特堅持認為手指應該通過用沉重的、有阻力的觸感演奏樂器來加強,不斷重複所需的練習,直到一個人完全筋疲力盡並且無法繼續上。肖邦絕對不想與鋼琴的這種體操治療有任何關係。” 並且:“肖邦發明了一種全新的鋼琴演奏方法,使他能夠將技術練習減少到最低限度。” (Eigeldinger 27)。鑑於這些評論,肖邦更喜歡普雷耶鋼琴也就不足為奇了,它比李斯特喜歡的埃拉德鋼琴 更輕盈、反應更靈敏。

He was concerned with developing hand position in a natural way. Thus, he says that C major, which he considered the most difficult scale pianistically, should not be introduced first. Rather, he suggests beginning with the B-major (RH) and D-flat-major (LH) scales in order to more naturally introduce the passing of the thumb—an understanding of piano technique from a piano-centered rather than music-theory centered approach. Chopin writes: ÒFind the right position for the hand by placing your fingers on the keys E, F#, G#, A#, B: the long fingers will occupy the high keys, and the short fingers the low keys….this will curve the hand, giving it the necessary suppleness that it could not have with the fingers straight.”

他關心以自然的方式發展手部位置。因此,他說,他認為在鋼琴演奏上最難的音階C 大調不應首先引入。相反,他建議從 B 大調 (RH) 和降 D 大調 (LH) 音階開始,以便更自然地介紹拇指的移動——從以鋼琴為中心而不是音樂理論的角度理解鋼琴技巧為中心的方法。 肖邦寫道: Ò將手指放在 E、F#、G#、A#、B 鍵上,找到手的正確位置:長手指將佔據高音鍵,短手指將佔據低音鍵……這將彎曲手,賦予它必要的柔軟度,這是手指伸直所無法獲得的。”

ChopinÕs method was predicated on what the student actually needed to know in order to play the piano. Chopin writes in the Sketch for a method: “People have tried out all kinds of methods of learning to play the piano, methods that are tedious and useless and have nothing to do with the study of this instrument. It’s like learning, for example, to walk on one’s hands in order to go for a stroll. Eventually one is no longer able to walk properly on one’s feet, and not very well on one’s hands either. It doesn’t teach us how to play the music itself—and the kind of difficulty we are practicing is not the difficulty encountered in good music, the music of the masters. It’s an abstract difficulty, a new genre of acrobatics.” (Eigeldinger 193)

肖邦的方法是基於學生實際需要知道什麼才能彈鋼琴。肖邦在《素描》中為一種方法寫道:“人們嘗試了各種學習彈鋼琴的方法,這些方法繁瑣無用,與學習這件樂器毫無關係。就像學習,例如,為了散步而用手走路。最終,一個人不再能夠正確地用腳走路,而且用手也不太好。它沒有教我們如何演奏音樂本身——以及我們正在練習的那種困難不是在好音樂、大師的音樂中遇到的困難。這是一種抽象的困難,一種新的雜技流派。” (艾格爾丁格193)

Chopin’s sketch for a method attempts to be very practical and simple, beginning from first principles: all music is either steps or skips (scalar or arpeggio patterns). From this he derives the idea that all you need to know how to do is play trills, scales, and arpeggios, in addition to chords of various numbers of notes.

肖邦的方法草圖試圖非常實用和簡單,從第一原則開始:所有音樂都是步進或跳躍(標量或琶音模式)。從中他得出的想法是,除了各種音符的和弦之外,你需要知道如何做的就是演奏顫音、音階和琶音。

The method also goes into the proper position, suggesting the elbows level with the keyboard. His pupils and associates report that both in teaching and in his own playing, he wanted the elbows relaxed and close to the body, and with a minimum of unnecessary movement. Of one pupil, Chopin is reported to have said that he is talented but still plays from his elbows! According to Jan Kleczynski, who collected reminiscences from a number of Chopin’s pupils, “For all rapid passages in general the hands must be slightly turned, the right hand to the right, and the left hand to the left; and the elbows should remain close to the body, except in the highest and lowest octaves.” (Eigeldinger 31)

該方法也進入了正確的位置,建議肘部與鍵盤齊平。他的學生和同事報告說,無論是在教學還是在他自己的演奏中,他都希望肘部放鬆並靠近身體,並且盡量減少不必要的運動。據報導,其中一位學生肖邦曾說過,他很有才華,但仍然靠手肘演奏!根據 Jan Kleczynski 的說法,他收集了一些肖邦學生的回憶錄,“一般來說,對於所有快速段落,雙手必須稍微轉動,右手向右,左手向左;肘部應該保持靠近身體,除了最高和最低的八度音階。” (艾格爾丁格31)

Chopin works from the idea that the finger initiates everything, the wrist is supple (29), and “the arm is slave to the hand.” Mikuli writes: “According to Chopin, evenness in scales and arpeggios depended not merely on equal strengthening of all fingers by means of five-finger exercises, and on entire freedom of the thumb when passing under and over, but above all on a constant sideways movement of the hands (with the elbow hanging freely and always loose)” (Eigeldinger 37) Chopin writes “No one will notice the inequality of sound in a very fast scale, as long as the notes are played in equal time” (Eigeldinger 37) –an important indicator of where his priorities lay.

肖邦的創作理念是手指是萬物之源,手腕是柔軟的 (29),“手臂是手的奴隸”。米庫利 寫道:“根據肖邦的說法,音階和琶音的均勻性不僅取決於通過五指練習對所有手指的均勻加強,還取決於拇指上下移動時的完全自由度,但最重要的是取決於恆定的側向手的移動(肘部自由下垂且始終鬆動)”(Eigeldinger 37)肖邦寫道:“只要音符在相同的時間演奏,沒有人會注意到非常快音階中聲音的不平等”(Eigeldinger 37 ) – 一個重要的指標,表明他的優先事項在哪裡。

Perhaps Chopin’s most important idea, one which was taught to me by Earl Wild many years ago, is that the second finger is the center of the hand. (Eigeldinger 18 elucidates extensions etc. in the etudes). I will show this idea with various examples from the etudes. The most obvious case is in op. 25, no. 3. Some less obvious examples include op. 10, no. 3 and op. 10, no. 4, which can serve to illustrate how all-pervasive this second-finger-centric philosophy is (and how practically applicable). Any arpeggiated passage (op. 10, no. 8; op. 25, no. 1) and many chordal passages (op. 10, no. 11 is an excellent case in point) serve to strengthen the second finger and achieve good balance. The accent pattern in the opening of the “Revolutionary” Etude (op. 10, no. 12) also forces the hand to roll through the second finger, actually making the passage easier to play. This idea comports nicely with Chopin’s desire for a hand position with the hands slightly turned out.

也許肖邦最重要的思想是厄爾·懷爾德多年前教給我的,第二根手指是手的中心。(Eigeldinger 18 在練習曲中闡明了擴展等)。我將用練習曲中的各種例子來展示這個想法。最明顯的例子是在 op 中。25,沒有。3. 一些不太明顯的例子包括 op。10,沒有。3 和操作。10,沒有。4,這可以用來說明這種以第二指為中心的哲學是多麼普遍(以及如何實際適用)。 任何琶音段落(op. 10, no. 8; op. 25, no. 1)和許多 和弦段落(op. 10, no. 11 是一個很好的例子)有助於加強第二根手指並達到良好的平衡。“革命”練習曲(op. 10, no. 12)開頭的重音模式也迫使手通過第二根手指滾動,實際上使樂段更容易演奏。這個想法與肖邦希望雙手略微外翻的姿勢非常吻合。

Chopin also made a point in his teaching of advocating the right fingering for every passage (Eigeldinger 19). There are numerous examples in students’ scores as well as in the published scores of the etudes and other works that demonstrate his philosophy of fingering. The B-flat minor scherzo is full of good examples as well, where the pattern is almost unplayable unless you understand the proper placement of the hand around the pivot of the second finger.

肖邦在他的教學中也提出了一個觀點,即提倡在每一段中使用正確的指法(Eigeldinger 19)。在學生的樂譜中以及練習曲和其他作品中已發表的樂譜中有許多例子可以證明他的指法哲學。降 B 小調諧謔曲也有很多很好的例子,除非您了解手在第二根手指的樞軸周圍的正確位置,否則該模式幾乎無法演奏。

Some of his musically-driven fingerings include playing the same finger on different notes while carrying the melody, playing repeated notes with one finger, and using numerous substitutions to encourage legato playing with a relaxed hand. Also toward a more relaxed hand position, he suggested trills with 1-3, 2-4, and 3-5 as being inherently more flexible and easier than with adjacent fingers.

他的一些 音樂驅動的指法包括在演奏旋律的同時在不同的音符上彈奏同一根手指,用一根手指重複彈奏音符,以及使用大量替換來鼓勵用放鬆的手演奏連奏。此外,對於更放鬆的手部姿勢,他建議 1-3、2-4 和 3-5 的顫音本質上比相鄰手指更靈活、更容易。

Some of Chopin’s suggestions for practice include moving from a gentle staccato to legato with simple patterns. One advantage of this was to demonstrate a more relaxed passing of the thumb, avoiding contortions of the hand in position changes (Eigeldinger 38). Chopin’s own legato was known for depth of tone and relaxed hand position. Chopin was also known to abhor overly loud or exaggerated playing.

肖邦的一些練習建議包括從柔和的斷奏過渡到具有簡單模式的連奏。這樣做的一個好處是展示了拇指的更輕鬆的傳遞,避免了手在位置變化時的扭曲 ( Eigeldinger 38)。肖邦自己的連奏以深沉的音調和放鬆的手部姿勢而聞名。眾所周知,肖邦厭惡過分響亮或誇張的演奏。

It is impossible to overemphasize Chopin’s adherence to developing technique only for a musical result. Chopin’s attitude to “evenness” is telling: he preferred to emphasize the individuality of the fingers, and made clear that light and fast playing eliminated the need for a forced evenness of touch. Mikuli writes: “Untiringly he taught that the appropriate exercises should not be merely mechanical but rather should enlist the whole will of the student; therefore he would never require a mindless twenty or forty-fold repetition (still today the extolled arcanum at so many schools), let alone a drill during which one could, according to Kalkbrenner’s advice, simultaneously occupy oneself with reading(!).”

怎麼強調肖邦都不會過分強調只為音樂效果而發展技術。肖邦對“均勻度”的態度很能說明問題:他更喜歡強調手指的個性,並明確指出輕快的彈奏消除了對觸鍵的強制均勻性的需要。Mikuli 寫道:“他孜孜不倦地教導說,適當的練習不應該僅僅是機械的,而應該激發學生的全部意志;因此,他永遠不需要盲目地重複 20 次或 40 次(直到今天,許多學校仍然在推崇奧秘),更不用說根據Kalkbrenner 的 建議,人們可以同時進行閱讀 ( !) 的訓練了。”

Chopin’s teaching and practice of rubato is important to elucidate. Many sources confirm that Chopin actually abhorred liberties of tempo. Mikuli writes, for example, “In keeping time Chopin was inexorable, and some readers will be surprised to learn that the metronome never left the piano.” Like Mozart before him, Chopin suggests that the accompaniment remains in strict time while the melody is free to work around it (this would be akin to the way jazz musicians handle time now). This indicates that the hands would not necessarily sound together at all times. Mathias writes, “you can be early, you can be late, the hands are not in phase; then you make a compensation which re-establishes the ensemble. In Weber’s music, for example, Chopin recommended this way of playing.” (Eigeldinger 49-50). Kleczynski adds, “This style is based upon simplicity, it admits of no affectation, and therefore does not allow too great changes of movement. This is an absolute condition for the execution of all Chopin’s works.” (Eigeldinger 54) In light of these comments, it is interesting to me that in the Third and Fourth Ballades (in contrast to the first two), Chopin’s compositional language has developed to the point that he indicates no changes of tempo (with the exception of a slight pi mosso at the end of the Third Ballade—it seems that he has reached a point of classical balance, and has striven to show changes of character more with the notation of note values than with changes of tempo. I believe this is reflective of his general “classical” attitude toward tempo. (Example: Raoul Pugno: Berceuse.)

肖邦的rubato教學和練習很重要。許多消息來源證實,肖邦實際上厭惡節奏的自由。例如,米庫利寫道,“在計時方面,肖邦是無情的,一些讀者會驚訝地發現節拍器從未離開過鋼琴。” 就像他之前的莫扎特一樣,肖邦建議伴奏保持嚴格的時間,而旋律可以自由地圍繞它工作(這類似於現在爵士音樂家處理時間的方式)。這表明指針不一定始終在一起發聲。馬蒂亞斯寫道,“你可以早,你可以晚,手不在相位;然後你做出補償,重新建立合奏。例如,在韋伯的音樂中,肖邦推薦這種演奏方式。(Eigeldinger 49-50)。 Kleczynski補充說:“這種風格基於簡單,它不允許做作,因此不允許動作有太大變化。這是執行肖邦所有作品的絕對條件。” (艾格爾丁格 54) 鑑於這些評論,令我感興趣的是,在第三和第四敘事曲中(與前兩首相反),肖邦的作曲語言已經發展到他沒有表現出速度變化的程度(除了輕微 的pi第三敘事曲末尾的 莫索——似乎他已經達到了古典平衡的地步,力求通過音值的記法而不是速度的變化來表現性格的變化。我認為這反映了他的一般對節奏的“古典”態度。(例如: Raoul Pugno : Berceuse。)

In terms of phrasing and articulation, the following remarks are important and instructive. Kleczynski summarizes: “A long note is stronger, as is also a high note. A dissonant is likewise stronger, and equally so a syncopated note. The ending of a phrase, before a comma, or a stop, is always weak.” (Eigeldinger 42). “Chopin attached great importance to slurs, which by the way are not always correctly drawn in the greater part of his works; whenever this mark terminated he detached the hand after having diminished the tone.” (Eigeldinger, 45)

就措辭和發音而言,以下評論很重要且具有指導意義。 Kleczynski總結道:“長音符更強,高音符也更強。不協和音同樣更強,切分音符同樣如此。短語結尾,在逗號或停止符之前,總是弱的。” (Eigeldinger 42)。“肖邦非常重視誹謗,順便說一句,在他的大部分作品中,這些誹謗並不總是被正確地描繪出來;每當這個標記結束時,他都會在減弱音調後鬆開手。” (艾格爾丁格,45 歲)

Physical demonstrations of the principles of playing mentioned throughout this paper are necessary to fully elucidate the practical implications of Chopin’s teaching philosophy. Although I have heard it said that Chopin’s school died with him, it is evident to me both through the teaching that I received from Earl Wild and Paul Doguereau and through the examples of Chopin’s grand-pupils that this is not the case. Chopin’s legacy and philosophy in fact do live on, and many of his most important principles—including practicing musically, practicing practically, practicing in limited doses, and developing a technique based on musical needs rather than on the need to demonstrate physical prowess—are central the teaching of many of us in the field today.

對本文中提到的演奏原理進行物理演示對於充分闡明肖邦教學理念的實際意義是必要的。雖然我聽說肖邦的學校和他一起死了,但我從厄爾·懷爾德和保羅·多格羅那裡得到的教導以及肖邦孫輩的例子都清楚地表明,情況並非如此。肖邦的遺產和哲學實際上仍然存在,他的許多最重要的原則——包括 音樂 練習、實踐練習、有限劑量練習,以及根據音樂需求而不是展示身體實力的需要開發技術——都是核心今天我們許多人在該領域的教學。

2. The Chopin Method: posture at the piano

3. The Chopin method: the piano hand

YouTube 上提供的肖邦孫輩的歷史錄音:

Moritz Rosenthal (1862-1946)(從 10 歲開始成為 Mikuli 的學生,後來與 Joseffy 和 Liszt 一起工作)

練習曲作品。10,沒有。5 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1s2q5E_Mfbc

D-降調夜曲。27,沒有。2 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=roN3aPBGoVs

升 C 小調圓舞曲,同前。64,沒有。2 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QmpbwCCm7Ws

瑪祖卡,同前。33,沒有。2 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ViwG5EhkMmM

瑪祖卡作品。24,沒有。4 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gRZe1qnOgfg

B 小調奏鳴曲http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=452q_6va-Eo

降 E 大調夜曲,同前。9,沒有。2 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X77Nm1nrcG8

Raoul Pugno (1852-1914)(馬蒂亞斯的學生)

降 A 大調肖邦即興曲http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7x4R8jU5zv4

肖邦貝西斯曲目http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w8tLnXw_rcI

肖邦葬禮進行曲http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4mYqyPdKHOU

肖邦夜曲 op. 15,沒有。2 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z3nq2WSxdTQ

Raoul Koczalski (1884-1948)(米庫利的學生)

夜曲作品。9,沒有。2 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VRmek8kADWA

3 Ecossaises http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JB_I9teLrPk

Trois Nouvelles 練習曲http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7zBDTIdWcTk

D 小調前奏曲http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4OnlqDeDoEs

第一敘事曲http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fac0bzmASgY

第 3 號敘事曲http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S53kvtRQ-wg

華爾茲作品。18 和操作。34,沒有。2 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LWpHK_9glEE

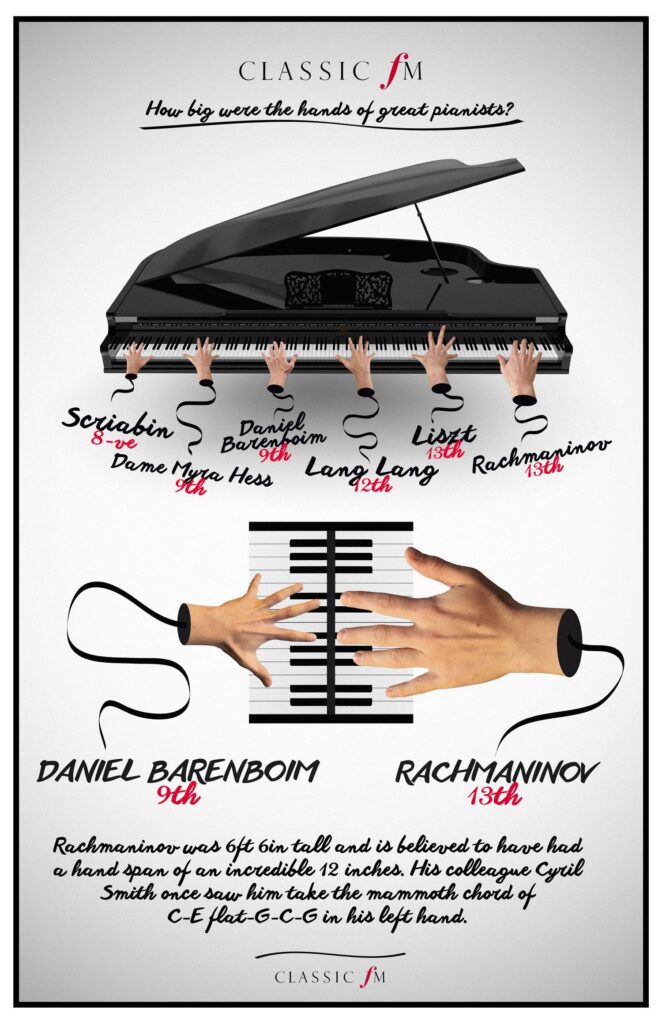

偉大鋼琴家的手的大小

您是否知道丹尼爾·巴倫博伊姆,他那一代最受尊敬的鋼琴家之一,可以在鋼琴上跨過 9 度,而拉赫瑪尼諾夫和李斯特可以跨過 13 度?

拉赫瑪尼諾夫身高 6 英尺 6 英寸,據信他的手掌跨度達到令人難以置信的 12 英寸。他的同事 Cyril Smith 曾經看到他用左手彈奏 CE flat-GCG 的龐大和弦。

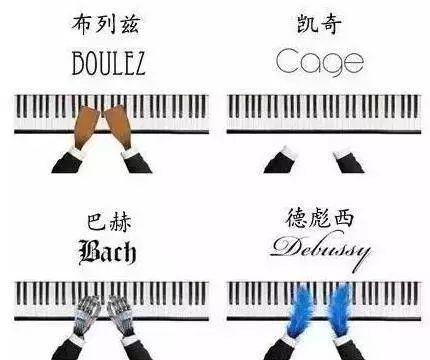

圖解歷史上的鋼琴大師們的手!

這八雙「腦洞大開」的手你們看懂了嗎?讓我們隨著這些手一起來認識一下這八位傳奇的鋼琴家!

蕭邦(Chopin):流動著的攪拌器

有「鋼琴詩人」美稱的波蘭作曲家、鋼琴家蕭邦的手被公認是「最優美的手」,他的演奏平穩有力,觸鍵勻稱,同時融合了各種情結:單純質樸的愛國情懷、傷感浪漫主義情懷,和聲和旋律處理都非常精緻。小夥伴們可以去聽一聽蕭邦的《革命練習曲》,親身感受下這種混合卻流動不止的演奏,恰如攪拌器持續的混融。

貝多芬(Beethoven):

力度!力度!在你心上用力地敲擊!

德國音樂家貝多芬《命運交響曲》中「命運」敲擊的動機,多像錘子敲擊的聲音。力度,力度,力度(重要事情說三遍)!用大錘敲擊形容貝多芬的音樂也算是有理可循吧!這裡,介紹一首貝多芬的晚期作品——《降B大調鋼琴奏鳴曲》(Op.106),世稱《「槌子鍵」鋼琴奏鳴曲》。聽過這部作品相信你一定會對貝多芬的錘子手有更深刻的體驗!

拉赫瑪尼諾夫(Rachmaninoff):

像章魚觸鬚般蓋住了鋼琴鍵盤

俄羅斯作曲家、指揮家、鋼琴家拉赫瑪尼諾夫有一雙大手!非常大!就是這得天獨厚的大手,使他的左手能很輕易地按到跨十二度的琴鍵。因此拉赫瑪尼諾夫的鋼琴曲並不是所有人都能彈奏的,特別是《第三鋼琴協奏曲》。據說,拉赫馬尼諾夫臨終的時候,曾看著自己的手說:「再見了,我的大手。」

李斯特(Liszt):

有多大跨度寫多大,撕裂你的虎口

匈牙利鋼琴之王李斯特的手,被公認是「又寬又大」。他的手指長而平均,自然伸張可達「十度」,在他的鋼琴作品中,有許多的連續十度進行。李斯特的演奏風格華麗恢弘,氣勢勁拔。其作品技巧之高超,彈過李斯特作品的夥伴們一定是飽受折磨吧。有人說彈《鍾》(《帕格尼尼主題大練習曲》中的第三首)不僅僅是撕裂虎口的問題,完全就是五指釘耙啊!

布列茲(Boulez):音塊木鏟般的音色

20世紀法國作曲家布列茲不但是位作曲家,還是位指揮家。作為梅西安的學生,布列茲繼承並發揚了十二音與序列音樂,無論是指揮或是創作都有著數理的嚴謹與詩意的揮灑。他的音樂作品結合了嚴密的數學構思與自由、主觀、甚至狂暴的情感表達,但他制定音樂規則時數學般的嚴格給了這些狂暴情感以必要的補償。聽聽布列茲的鋼琴奏鳴曲,你便可以發現如音塊木鏟般的音色。

凱奇(Cage):玩的就是情懷……

20世紀美國著名作曲家、哲學家和音樂家約翰·凱奇,作為「偶然音樂」的代表人物,以嚴肅的思考、獨特的行為方式去探求音樂的新發展。其最經典作品《4』33》或是解讀圖上「無手」的最好例證。《4』33》共三個樂章,總長度4分33秒,樂譜上沒有任何音符,唯一標明的要求就是「Tacet」(沉默),體會在寂靜之中由偶然所帶來的一切聲音。這也代表了凱奇一個重要的音樂哲學觀點:音樂的最基本元素不是演奏,而是聆聽。「無手」或就是在一無所有的狀態下,坦然地擁抱所有最純粹的、自然發生的音吧。

巴赫(Bach):精密如機械

約翰·塞巴斯蒂安·巴赫是巴洛克時期德國最偉大的作曲家之一,他是一位真正精通作曲技法的大師,我們可以在他的復調作品中發現大量的聲部交叉和對位旋律。巴洛克時代追求空間律動帶給我們了強烈效果,如巴赫的《哥德堡變奏曲》,有著異常縝密的邏輯,節奏、音色和音響都有非常精準的分寸把握,精密的背後卻一點都不缺少趣味性。

德彪西(Debussy):如夢如幻,輕如鴻毛

20世紀印象主義音樂代表人物法國作曲家德彪西的音樂充分發揮了音樂想像力,拓展了聲音的表現空間。德彪西代表作前奏曲《牧神午後》就描繪了一個慵懶的魔幻夢境,沒有大起大落的戲劇衝突,一切都是淡淡的,感性的,籠罩了一層朦朧的色彩。